I’m interested in wildlife conservation with special focus on endangered species management, landscape change and it is impacts on wildlife. Specifically, I study how species thrive in human-modified landscapes with the aim of developing best management strategies that integrate conservation with human livelihoods.

I work in areas along the Kenya-Somalia border and the Horn of Africa region which has heavily been impacted by human activities including landscape change, overgrazing and climate change.

https://www.hirolaconservation.org/

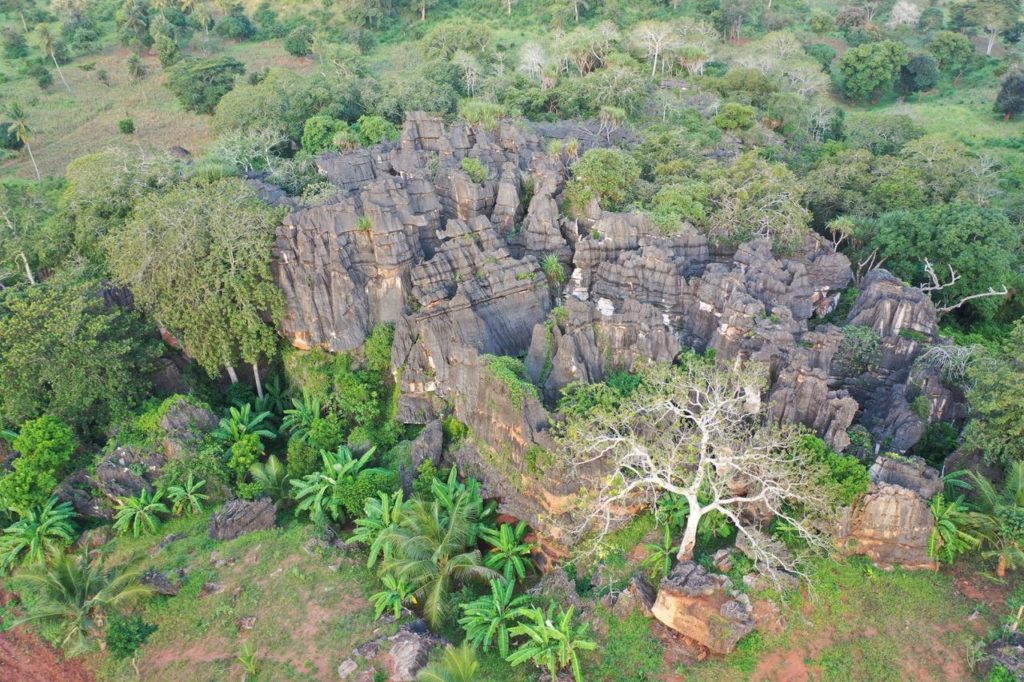

I work on central African and Gabonese biodiversity of Amphibians, in order to protect their populations and their habitats. My work consists of knowing biodiversity, understanding the relationship between the different constituents, understanding the impact of human activities on biodiversity, understanding the causes of its decline and finally participating in its conservation. Our Work helps to protect Amphibians’ landscapes and their health.

In Gabon, the combination of protecting elephants, which increases their populations and deforestation by logging companies leads to human-wildlife conflicts, which causes elephants to destroy plantations in villages, which could lead to poaching. The rural exodus has already started in certain villages.

This project is one of the potential tools used in order to envision the conservation status of Avifauna within and specific landscapes where there are human populations.

I remember meeting some hunters who were specifically hunting (any) ringed birds during their migration season in few parts in Sudan. One hunter claimed to have over 500 pieces of rings taken from birds shot by him only; all of them were doing it because they think that the metals used in birds ringing can be sold in the future. I believe that such activities directly affect (already) any ongoing and future research projects as well as the conservation status of over 15 different migratory birds’ species. Sudan is known to be one of the most active migration routes for birds from more than 3 continents including all of Africa and even more future possibilities of new migrations due to climate change. It had zero impact on the well-being of those hunters apart from having more BBQs, and savings, and a few visiting trophy hunter from time to time depending on the (season). This is one of the few definite impacts of such activities conducted by mostly local communities and tourist agencies lately. Such activities also come with gold mining inside core zones of protected areas, logging (habitat destruction), and uncontrolled agricultural activities both inside and outside national parks.

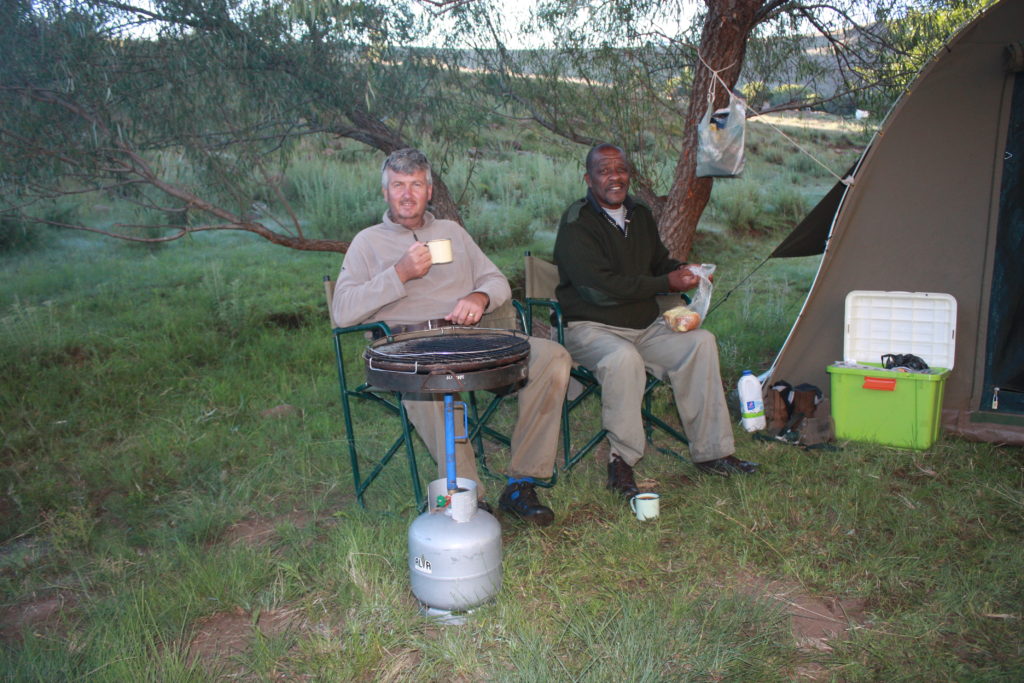

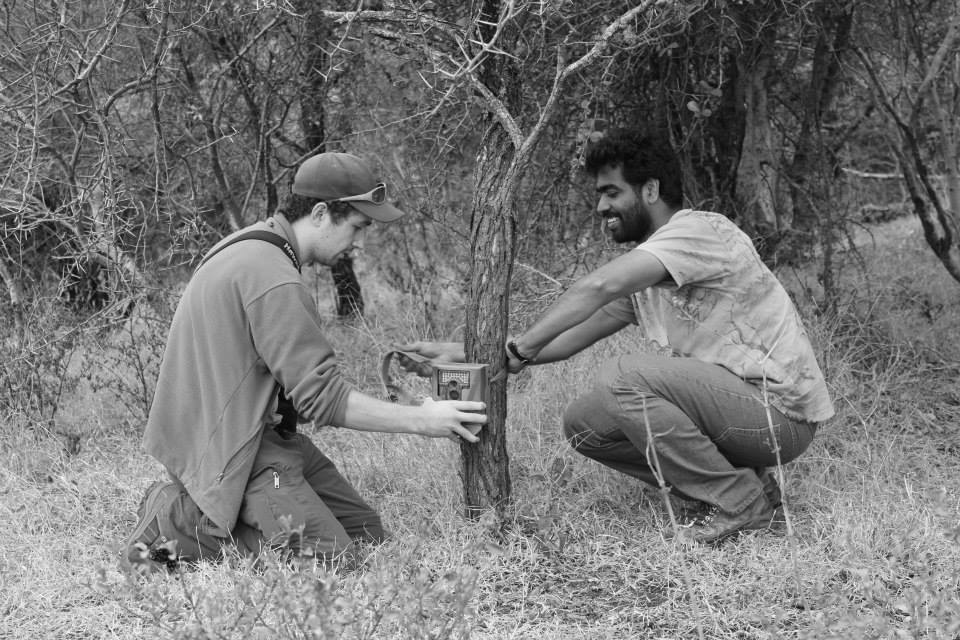

I have been fortunate to work on African mammal biodiversity across several countries including Angola, Botswana, Djibouti, and Kenya as well as traveling to various other countries for research or wildlife viewing. My specialization is small carnivores with a focus on documenting biodiversity patterns and disease in these and other mammals including rodents, bats, and insectivores Our work is helping elucidate patterns of mammalian biodiversity at the local and country-wide scale through intensive museum-based surveys and research.

I have seen first hand how human activities/land use impact biodiversity with direct research focused on small carnivore behavior and parasite burdens in East Africa as well as more general biodiversity surveys across various countries. For example, we found that small carnivores living in human-dominated systems maintain larger home ranges than those living in adjacent, uninhabited habitats, but that small carnivores living in protected areas had greater tick burdens. The interactions between small carnivores and domestic carnivores has direct implications for transmission of human rabies in this system and we are working to better understand the interplay between the domestic and sylvatic cycle across this landscape.

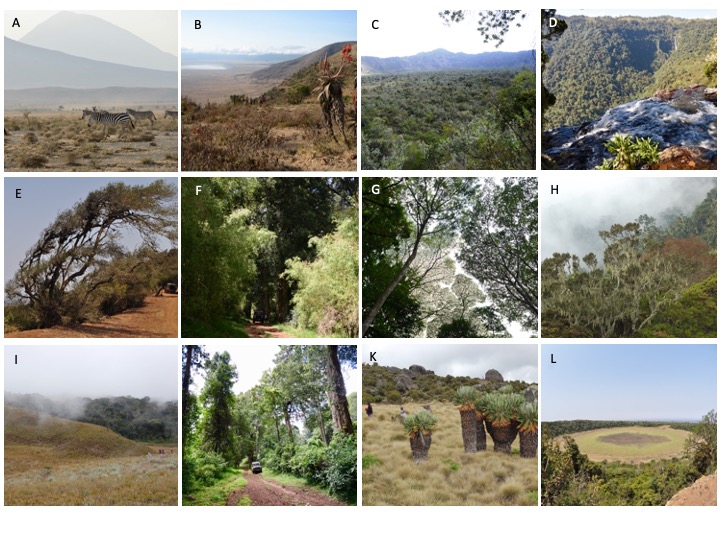

Dr. Addisu Mekonnen’s research focuses on understanding the responses of wild primates to a variety of anthropogenic and natural factors and their consequences, and the causes and consequences of diversity in ecology, behaviour, genetics, evolutionary biology, and key life-history traits. My research integrates fieldwork (ecology and conservation), laboratory work (genetics), and geospatial analyses (GIS and remote sensing) to design conservation and management strategies. I conduct my research primarily in southern Ethiopia, where I am a director of the Bale Monkey and Bamboo Research Project, which is a long-term field study (15 years) in the Odobullu Forest of the Bale Mountains and two fragmented forests in the Sidamo Highlands. I also conduct other primate and wildlife research projects in Ethiopia.

I am interested in studying systematics and evolution of afrotropical small mammals including rodents (mostly) shrews and bats. I use first morphology and molecular taxonomy to test the status of species known from a few number of specimens and to tackle the problem the existence of a cryptic diversity in small mammals. I use also Phylogenetics and evolutionary biogegraphy to assess mechanisms acting in biodiversity promotion in afrotropical forest and in particular mountain areas. I am also interested in conservation issues in those specific ecosystems.

Before the increase of the human population and the development of agriculture in the 20th century, the Banso-Bamenda Highlands area, within the Cameroon Volcanic Line, was completely covered with forest. From 20,000 ha in 1978 but it had been reduced to 9,500 ha by 2012. The Kilum-Ijim forest in Mount Oku (3011m asl), within the Banso-Bamenda Highlands area, is the largest remaining patch of Afromontane forest in West and Central Africa. Located in an area with a high human population density, it is object of intense pressures on natural resources. Threats to biodiversity include overgrazing by cattle and goats in grassland areas and montane forests, firewood harvesting, agriculture, bee keeping, debarking of Prunus trees for medicinal uses, and bushmeat hunting. Mount oku is known for its rich diversity of endemic plant and animal taxa. It harbours seven species of rodents endemic to the Banso-Bamenda Highlands, of which four are strictly restricted to the mountain, all are categorized as Vulnerable or Endangered on the IUCN Red List, with a decreasing population trend. We found that after extirpating large and medium size mammals, rodent trapping in Oku village requires conservation attention; the high pressure on endemic mammals, combined with forest destruction, can lead to the extinction of the endemic rodent genus Lamottemys, restricted to an area of 100 km2 in the montane forest.

My research focus is on South Africa’s endemic birds, particularly the Fynbos and Karoo biomes.

The birds of the Fynbos biome are particularly negatively impacted by human activity, particularly agricultural encroachment (ploughing). However, Karoo birds benefit from human presence, as this is an arid zone, where small livestock farmers provide water and food.

Have worked on African carnivores in the wild since 31 years for PhD and post-doc research in South Africa, Namibia, Swaziland (aardwolf, black-footed cat, African wildcat, arid habitat mongoose, mustelids, canids), a for 5 years in the Moroccan Sahara (sand cat, canids, mustelids). As a curator of two scientifically led zoos in the past 23 years I also facilitate and perform research on captive carnivores, particularly intensively for the felids (IUCN Cat SG member) and link to in-situ projects.

It has a profound impact, particularly for human-wildlife conflict species (black-backed jackal, caracal, leopard – collateral damage to smaller carnivores like black-footed cat, African wildcat, Cape fox) through indiscriminate control measures by the farming community. Overgrazing, encroachment, disturbance, termite control, direct persecution. Also the association of domestic carnivores (feral and shepherding dogs, domestic cats) with human presence – impact via disease transfer and also predation/killing.

I am a behavioural ecologist specialising in the behaviour of small carnivores such as yellow mongoose, bat-eared foxes, and black-backed jackal. My past research includes work on social primates and whistling rats. I am very interested in decision-making as affected by different types of risk, which includes the interaction between humans and small carnivores. Anthropogenic habitats pose both risks and rewards to small carnivores, while increased interspecific contact may also expose humans to more zoonotic pathogens. To uncover patterns of small-carnivore behaviour at a larger scale, I am currently engaging in more collaborative research across study sites and species.

Very often, small carnivores do well in disturbed habitats, where their social behaviour may increase. Although this social (and dietary) flexibility is not detrimental to the small carnivores per se, it does tend to increase the circulation of pathogens in their populations, and by extension also exposes humans to more risk from the zoonotic disease.

Andrew holds an MSc from the University of Cape Town. His thesis was conducted through the FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology and focused on the effects of boat-based tourism on waterbirds. Andrew has experience as a professional bird guide and ornithologist, working for BirdLife South Africa for over 6 years on penguins and avitourism (during which he made contributions to this study). In 2024, Andrew transitioned into politics, taking up a seat as a Member of Parliament and serving on the Portfolio Committee for Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment.

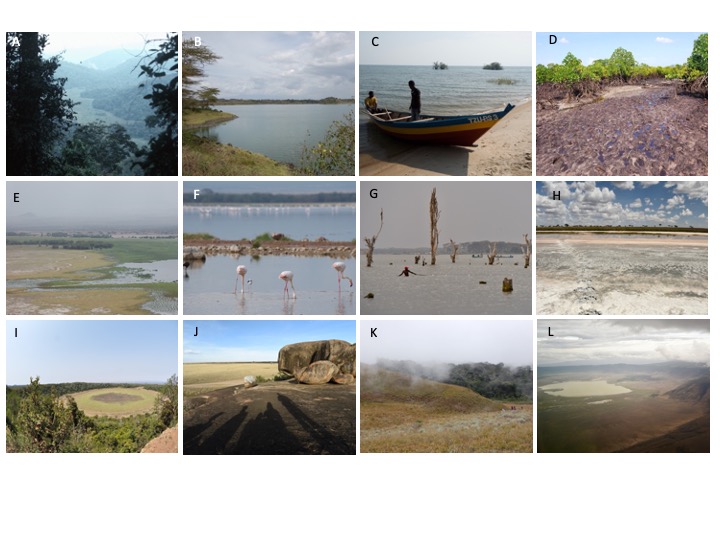

Andy is head of the Key Biodiversity Areas (KBA) Secretariat. The KBA Secretariat supports the implementation of the KBA Programme focused on identifying, mapping, monitoring and conserving sites of importance for the global persistence of biodiversity. He has worked extensively in East and Central Africa where he supported the establishment of new protected areas through biological and socio-economic surveys and engagement of members of local communities. He also supported protected area authorities to better manage and conserve their protected areas in this region.

http://www.keybiodiversityareas.org/

I am an ecologist with experience across most of southern Africa, as a researcher, planner and consultant. I currently lead national scale biodiversity assessment and reporting for South Africa. My personal research interests are on ecosystem mapping and red listing, Key Biodiversity Areas and biodiversity indicators.

Land use change in the Eastern Cape over the last 20 years has been very interesting to watch – the switch to game farming and tourism-based land use has profound impacts on biodiversity – not all good. The changes to land ownership patterns and rural livelihoods have been substantial.

ResearchGate | Twitter | LinkedIn

I worked on aardvarks many years ago and am currently Chair of the IUCN Afrotheria Specialist Group.

There is evidence (not from my own work though) of climate change impacting aardvarks in very dry areas like the Kalahari.

I am interested in biodiversity in its broadest sense and how it evolves. I have a particular fondness for amphibians and reptiles (including birds) and their conservation and have recently been concentrating my efforts on the threats posed to Western Cape biodiversity by invasive alien species and altered fire regimes.

In the Western Cape Province of South Africa there has been a serious invasion of the catchment areas of human introduced invasive alien pines and other tree species which increases shade relative to indigenous vegetation (not good for most reptiles), outcompetes indigenous vegetation (which directly reduces plant diversity and negatively affects the animals which are adapted to the indigenous vegetation), increases fuel load during fires which can lead to hotter an longer-burning fires which again affects plants and animals negatively and finally seriously reduces surface water runoff which is bad for biodiversity and people living in water-stressed area.

Research on West African vegetation, biodiversity, sustainable use of plants, carbon sequestration, desertification and conservation. Also focus on ethnobotany and people’s uses of plants and view on vegetation changes in their local environment. The research has an applied and multidisciplinary approach and also covers tree planting in collaboration with local communities.

Many studies show that native tree populations in West Africa experience degradation and lack of regrowth caused by over-exploitation and cutting of valuable species, fire impact on savanna trees and gallery forests in the Sudanian zone and continuous browsing of trees in the Sahelian zone. This is also consistently mentioned by people living in rural communities in West Africa.

Dr. Benjamin Wigley is a South African ecologist known for his research on African savanna ecosystems, biodiversity, and climate change impacts. His work focuses on the interactions between vegetation, fire, herbivory, and land use, particularly in Southern Africa. By improving understanding of ecosystem dynamics, his research informs conservation planning and sustainable land management, contributing to the resilience of biodiversity-rich areas in a changing climate.

Dr. Benjamin Wigley’s work in the savanna landscapes of Southern Africa offers a clear example of how land use impacts biodiversity. His research shows that overgrazing, removal of fires and changes in land use practices can result in increased woody cover (especially encroaching shrub species) and alter fire regimes, leading to habitat degradation. These ecological changes can negatively affect human well-being. For example, biodiversity loss reduces ecosystem services such as grazing for livestock, and natural buffers against drought.

Benneth Obitte is a conservation ecologist whose research interest centers around the human dimensions of conservation. Specifically, Ben focuses on understanding the impact of anthropogenic disturbances on the ecology of bats, as well as disentangling the human behavioral drivers of these disturbances. Ben is currently a doctoral candidate at Texas Tech University. He is the co-founder and Director of Conservation programs for Small Mammal Conservation Organization (SMACON), an NGO registered in Nigeria. SMACON Protects small mammals and their habitat across West Africa through capacity strengthening and evidence-based conservation that safeguards local livelihoods.

https://www.smacon-africa.org/

I direct a Center that makes biodiversity data available for policy and management. Our projects include creating the Rwanda Biodiversity Information System, developing biodiversity indicators for freshwater ecosystems, and understanding buffer zone management approaches.

Yes, in buffer zones and land use type. Some buffer zones effectively extend area of the national park and are used by primates, Buffer zones around national parks are usually managed to exclude people, and since population density is so high and land limited, there is potential for multiple use in buffer zones that could benefit biodiversity and people, but he exclusion policy has negative impact on well-being.

LinkedIn | ResearchGate | Twitter

https://coebiodiversity.ur.ac.rw/

Researching samango monkey populations in South Africa’s Soutpansberg mountains since 2006, I have investigated their role in seed dispersal maintaining floristic diversity and regeneration, their spatial ecology focussing on utilisation of both naturally and anthropogenically fragmented habitats their population dynamics and regional phylogenetics. My work has always included dedicated public participation, education and conservation foci. I am currently interested in the impact linear infrastructure has not only on the samango monkey but on all five South African primates. As samango monkeys are forest specialists, my research interest extends to the roles of other forest mammals and indigenous forest conservation.

The main human activities impacting primate species in the area I work in are subsistence and commercial farming and linear infrastructure. Roads and power lines have a substantial impact on local primate populations by causing mortality and potentially forming barriers to dispersal for the smaller strepsirrhines. Human-primate interactions in agricultural and, to a lesser extent, urban areas are also common and often times lead to conflict with damage causing animals and considerable and under-reported mortality through targeted killing. Direct land transformation in some areas through rapid clearing of forests and savanna woodland for fuelwood and agricultural expansion as well as afforestation through exotic silviculture all exacerbate the influence of already naturally fragmented habitat patches occupied by the five primate species occurring. Strong biome shifts, potentially negative for some primate species, are already observed for parts of the region as a result of past and current anthropogenic drivers (extirpation of large herbivores, rapid biological invasion and altered fire regimes) and such shifts are predicted to be particularly intense for the region under most future global warming representative concentration pathways. Rapid social and environmental change, persistent poverty and constrained natural resources (particularly water) negatively impact on the well-being of people in the region.

https://www.facebook.com/LajumaResearch/

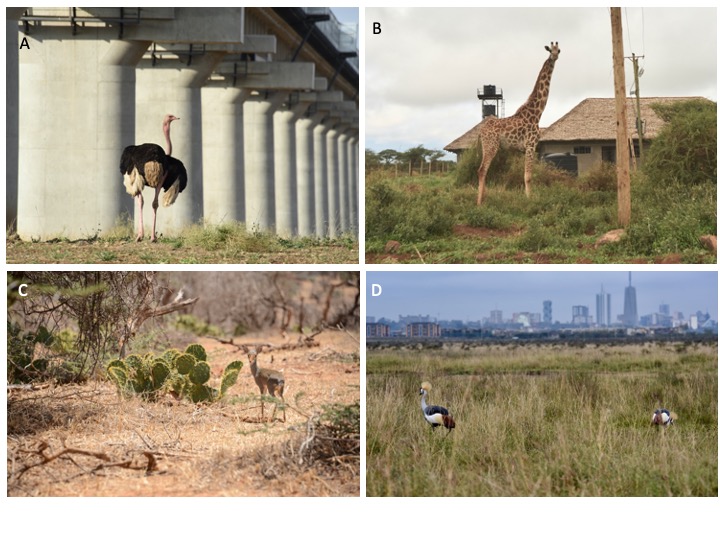

As the planet is becoming human-dominated there is an emergence of entirely new sets of habitats which nature has not seen before and there and there exists a gap knowledge and understanding of how wildlife species evolve and adapt to these increasing human-dominated and modified habitat (towns, cities and agricultural plantations. My research focuses on studying the evolutionary change of urban wildlife, in order to increase our understanding of the evolution and species which is vital in improving wildlife conservation, and inform green planning, development, and design and to improve pest and disease management in human-modified habitats.

My ongoing research shows that mice communities occurring in urban areas, sugarcane plantations and rural areas have reduced species richness and diversity compared with communities occurring in savanna habitats. My data also shows that anthropogenic habitats are dominated by generalist mice populations (e.g. the natal multi-mammate mouse) compared to savanna. The genetic data shows positive selection in genes involved in lipid and carbohydrate metabolism in the natal multi-mammate mouse (Mastomys natalensis) occurring in urban habitats. I hypothesized that selection is acting on metabolic pathways due to the new dietary composition linked with urban environments compared with adjacent less disturbed rural/natural habitats.

LinkedIn | ResearchGate | Twitter

My research work can be summarized in three areas: (i) sustainability and impact of of bushmeat hunting on ecosystem functioning; (ii) wildlife and food security in the context of climate change; (iii) ethnozoology and public health risks at human and wildlife interface. I am member of the Beninese Young Academy of Sciences and an affiliate member of the World Academy of Sciences, author and co-author of about 40 scientific articles published in the world class journals, I am also a member of several international associations, including the World Commission on Protected Areas and the International Union of Forest Research Organization.

My research typically focusses on how changing landscapes effect biological communities, and birds usually take centre stage as an excellent tool for understanding these effects. More recently I have begun studying birds and bees in the urban landscapes of Johannesburg to unpack how people in cities interact with biodiversity. As a research group we are focused on using open access and citizen science data to ask questions at broad scales.

I conduct research in the savanna ecosystems of Tanzania, with a focus on the Tarangire, Katavi-Rukwa, and Yaeda Ecosystems. The aim of my work is to contribute to the conservation of African biodiversity and to enhance the wellbeing of both wildlife and human communities. My research approach involves conducting longitudinal wildlife monitoring across these ecosystems to evaluate the effectiveness of protected areas, administering questionnaire surveys to understand local knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding wildlife species and zoonotic diseases, and testing locally adapted and culturally accepted interventions to reduce negative human-wildlife interactions. By implementing these research initiatives, I hope to contribute to sustainable human-wildlife coexistence in Tanzania.

My African biodiversity work has mainly been on small mammals taxonomy in the present and in the past. Morphological evolution and small mammals communities studies. My main areas of interest are mountains rodent and shrews of west-central Africa (Mt Nimba, Cameroon Volcanic Line) and eastern african savannas.

Deforestation by using fires is terrible for small mammals biodiversity especially for gallery forests in savannas environments. In Oku Mount small mammals are now eaten after the disappearance of large mammals, the unique mountain forest is no more regenerationg and is over grazed by domestic cattle. In Mt Nimba , iron mining activities destroy hectares of edaphic savannas and refuge for endemic bats.

Claude primarily focuses on wildlife ecology, conservation, and infectious disease surveillance, with a particular emphasis on bats. Wildlife Ecology and Conservation: He uses bat functional traits—such as flight and dispersal ability, acoustic signals, and genetic diversity—as tools to address evolutionary questions. His research investigates how environmental factors, including forest structure, topography, temperature, and rainfall, shape patterns of bat adaptation across Afrotropical landscapes. As part of wildlife conservation efforts, he is studying population trends and the conservation status of the endangered Kisangani red colobus (Piliocolobus langi), also known as Lang’s red colobus, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Infectious Disease Surveillance: He is focused on the inhabited forest regions of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where emerging infectious diseases such as orthopoxviruses and filoviruses are thought to circulate periodically among wildlife populations. He is developing a comprehensive, integrated approach combining bat surveys and large mammal monitoring to improve our understanding of how changes in biodiversity influence the risk of zoonotic disease spillover.

Dr. Chapman’s research focuses on how the environment influences animal abundance and social organization and given their plight, he has applied his research to primate conservation. He is a Wilson Center Fellow, Killam Research Fellow, Velan Foundation Awardee for Humanitarian Service, and is a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. In 2018 he was awarded the Konrad Adenauer Research Award from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation and an Office of an Academician, Northwest University, Xi’an, China. In 2019 he took up a position at George Washington University to allow him to more time for his conservation efforts. For the last 32+ years, Dr. Chapman has conducted research in Kibale National Park, Uganda. During this time, he has not just been an academic, but has devoted great effort to help the rural communities, establishing schools, clinics, a mobile clinic, and ecotourism projects. He has published 540+ articles, been cited 45000+ times, has a H factor of 107 (Google Scholar).

For the last 32+ years my project has collected data on the forest, animal populations, and human communities affecting Kibale National Park, Uganda. We have revealed a complex picture of change, where climate change, regional economic pressures, disease, nutrition, and human extractive practices all effect the primates and large mammals of the park. I have been engaged in conservation programs to help curve illegal activities, including establishing a chimpanzee ecotourism, community based ecotourism, clinic and mobile clinic to create a union between health care and conservation, school programs and education centers, and more. These activities have had a positive effect and the forest is regenerating and almost all of the primates and large mammal populations have grown substantially.

My work involves planning, implementation and restoration of conservation areas within the urban context of the Fynbos Biome.

Urban infrastructure, such as roads, sewer and power lines result in not only fragmentation of natural habitat but “edge effects” that extend their influence in to ecosystems. Even in well managed city’s, edge effects can significantly impact on biodiversity in protected areas. This is particularly relevant in landscapes of low nutrient and high diversity. Urbanisation also disrupts ecosystem drivers such as fire, hydrology or large scale herbivory; these then need to be mimicked.

Much of my African biodiversity work has been about surveying mammals, particularly under-sampled groups such as bats. I have also been particularly interested in the biodiversity by-catch of much of my camera trapping work on large carnivores in the southern African sub-region.

It would appear that the increase in the human population has started to manifest in terms of changes in animal behaviour at many of my study sites with several species shifting their main periods of activity away from when humans are more active.

I have spent more than a decade studying African pangolins, during which time I have been privileged to travel widely in Africa, and have seen three of the four African pangolin species in the wild. In addition to my pangolin-related work, I have also done several surveys of amphibians, reptiles and birds in southern, Central and West Africa.

I study the ecology of plants, particularly the herbaceous (non-woody) component of tropical and subtropical savannas and grasslands in north-eastern South Africa, and how these systems are impacted and defined by various disturbances, including fire frequency, herbivory, alien invasive taxa, nutrient flux, and climate extremes. These grassy biomes underpin critical ecosystem services and functions, and my research is focused on better understanding plant population dynamics and predicting the potential negative effects imposed by land-use intensification, inappropriate land management, and climate change.

South African grasslands are species rich botanically, as is the often over-simplified view of the non-woody component of local savannas. These herbaceous communities are co-dominated by grass and forb species (wildflowers) which make significant contributions to the overall floral diversity and abundance. Natural and anthropogenic ecological disturbances, including fire, herbivory, alien invasive taxa, nutrient flux and climate – particularly when acting in combination – strong govern community composition and dominance, taxonomic and functional diversity, and productivity of these systems, as well as the critical ecosystem services (e.g. climate and water regulation, carbon sequestration) and functions (e.g. forage for livestock, wildlife and people, provision of habitat) that they support. Disturbance extremes outside the bounds of what is considered ‘normal’ – for example complete fire suppression, over-grazing, or frequent severe drought, act as ecological filters which result in depauperate and functionally-depressed communities.

l have spend the past 40+ years working in the field of southern African ornithology based in the spheres of a provincial conservation agency, a university (University of Cape Town) and a museum. My research interests have been broad, as reflected in my contribution to the Southern African Bird Atlas Project which covered all avian species in the region and my museum work which similarly covers the full range of avian diversity. My career stated in conservation and this has remained a focus throughout my subsequent work.

One striking example of a human activity/development/land-use change impacting biodiversity with which I am familiar is the impact of large dams and associated infrastructure on the highlands of Lesotho. These massive engineering projects not only have a direct impact in terms of huge areas inundated and downstream flows affected, they also introduce a myriad of additional infrastructure that have equally negative effects, e.g. roads, powerlines, etc. It is a sound lesson in how biodiversity is often best protected through inaccessibility. It is unclear how much these developments, designed to benefit people distance from the highlands, improve the well-being of the folk living in the highlands and arguably the ‘owners’ of the resource being exploited by outsiders.

I am a conservation ecologist currently conducting research at the School of Life Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal. I am interested in landscape and functional ecology, forest and grassland ecosystem functionality, and the effects of anthropogenic disturbance on community assemblages, with specific reference to bird and mammal communities.

Although my main research interest has been seabird ornithology and conservation, nowadays I am mostly land-based where I lead birdwatching tours across the African continent and have co-authored a popular field to the birds of Southern Africa. Through the bird tours I lead and through the publication of the field guide, I enjoy contributing to the ever-increasing understanding of African biodiversity.

As a bird tour guide I spend large amounts of time out in the field which has enabled me to gain a good understanding of how birds (in particular) are impacted by changing landscapes. Perhaps the best example I can think of, is how the birds have been impacted (mostly negatively) by ever-expanding industry and increasing human presence in and around Richards Bay, in northeastern South Africa. Many of the pans and lakes in the area used to be a haven for waterfowl and other water-associated bird species however most have left in recent years.

https://www.birdingecotours.com/

I am interested in broad aspects of wildlife conservation in anthropogenic ecosystems. My current research is on effects on wildlife biodiversity of various anthropogenic drivers of global change, including prescribed fire, livestock management, and large mammal extirpation

Dr Duncan MacFadyen has worked as head of research and conservation for E Oppenheimer & Son and then Oppenheimer Generations since 2002. The research entity supports, funds, and facilitates national and international researchers to conduct cutting edge research focused on the natural sciences. Duncan passion for small mammals was developed through his work as curator of mammalogy at the Ditsong Museum of Natural History in Pretoria, as well as through his MSc on small mammals in the northern plains of the Kruger National Park, and PhD in small mammal ecology in the Bankenveld grasslands. Duncan’s interest includes small mammal ecology, with specific focus on South Africa bats, rodents and insectivores.

The work has focused on the impact of management, land-use, herbivory and fire on small mammal diversity, species richness and abundance in various parts of South Africa. These have resulted in various shifts in rodent populations. In some cases these impacts have positively affected species, in other cases negatively.

https://www.ogresearchconservation.org/

I am the Founder and Managing Director of Reptile and Amphibian Program – Sierra Leone (RAP-SL). I work towards the documentation, protection and conservation of reptiles and amphibians of Sierra Leone and also do take action for the protection and conservation of Sierra Leone’s biodiversity especially threatened and endangered species in the country.

Farming and mining are the key activities impacting the population of species in Sierra Leone. These activities, in combination with other human influences have resulted in habitat degradation thereby resulting in species depletion. The impact of habitat degradation and decreased species populations on human well-being is immense within the region. Most of the above activities are contributing to global warming and climate change thereby affecting the well-being of humans. The sad thing about the large scale farming and mining is that about 99% of the products are exported while locals (human and wildlife) remain to suffer the consequences of the activities.

With Nature Tanzania (a national membership NGO working in Tanzania mainland) I support coordinattion, monitoring and evaluation of conservation projects and programs. I engage mostly in protection of Important Bird Areas (IBAs) and Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs). Many KBAs and IBAs face conservation challenges because of not being fully protected, hence at exposure to degradation. So, the communities are the centre of our work. We work with them in all projects mainly promoting conservation awareness, environmental education, active landscape/habitat restoration, species monitoring and empowering communities on improving community finance as part of reducing community’s dependence on natural resources.

Serious decline of vultures populations and narrowness of their distribution range in Mara-Serengeti ecosystem. The increase in human settlements, expansion of agricultural lands and grazing areas has significantly contributed to the rapid decline of population of seven species of vultures in the Mara-Serengeti ecosystem particularly in Makao Wildlife Management Area. Human well-being is also affected as agriculture and grazing are not climate smart agriculture adoptive. This drives utilisation of the natural resources without a proper plan, hence leading to reduced productions, climate change, etc.

Elie Tobi has been involved in the Reptiles and amphibian’s assessment in Gabon in the Gamba Complex of Protected Areas and along the Ogooué River course. These studies fostered the following:

1- Increasing the biodiversity knowledge

2- Understanding of the processes between human activities and ecosystems

3- A tool for biodiversity management through recommendations to the companies and national environment managers.

4- A useful baseline of data for biodiversity monitoring.

5- A tool for awareness and education raising.

6- Determining key areas for conservation and establishing conservation priorities.

Gabon is on central west coast of Africa (Lee et al. 2006). In 2000, Shell-Gabon entered into a partnership with Smithsonian Institution, Monitoring and Assessment of Biodiversity to raise and increase the biodiversity knowledge in order to assess the impact of the hydrocarbon activities in the Gamba Complex of Protected Areas (CAPG) and make recommendations to monitor and mitigate human activities disturbances. Before the nineteen sixties, there was no town called Gamba. With the discovery of oil in the area in the sixties, people converged from around the world and settled in Gamba, a remote locality in the southwest of the country. The demography exploded up to 10.000 inhabitants. To date, the impact of such an installation is not under control. The situation is worsened by poorly fertile sandy soil which forces the population to shift to slash and burn agriculture increasing human-wildlife conflict. Coupled with poaching, the Nile crocodile is only found now in the coastal lagoons where they are also victims, along with the Central African Slender Snouted crocodile, of bycatch in fishermen nets. Studies are showing that Gamba has the lowest amphibian specific richness of the CAPG. The consequence is more insects and more diseases.

My research focus is on applied ecology with the aim of conserving ecosystems. My primary focus is on large herbivores, which are often understudied in favour of charismatic megafauna but form a vital part of every ecosystem.

Changing land use away from natural, protected areas can disrupt migrations and prevent connectivity between wildlife populations. Management interventions in natural areas without due consideration of potential consequences can damage ecosystem functioning, such as the provision of artificial water in seasonally dry areas.

My work is mainly on endangered species management and collaborative resources management leading to better wildlife tolerance in fringe communities.

Agriculture and recently mining activities in the high forest zone of Ghana are negatively affecting wildlife habitat. These activities have caused serious wildlife habitat encroachment and fragmentation leading to increasing human-wildlife conflicts.

I am a wildlife biologist specialising in the natural history, ecology and conservation of small carnivores. I am particularly interested in their spatial ecology, activity rhythms, diet and social organization. The acquired knowledge allows us to better understand niche partitioning and the potential impacts of top-down and bottom-up processes on these species, and conversely their potential impact on their predators and prey. Ultimately, a better understanding of both species natural history and ecological processes may help identify conservation needs and devise conservation actions.

I have so far mostly worked in Protected Areas (PAs), focusing on otherwise quite flexible small mammal species. Despite noticing drastic habitat differences between PAs and e.g. neighbouring livestock farms, most of the studied species are still present there, sometimes likely at similar densities. In some cases, the absence of medium-size predators may even favour the smaller carnivore species. It is also well-known that some generalist rodent species thrive in cropland areas, whereas specialists tend to be extirpated. I did not have the “opportunity” to observe the impact of human activities on the well-being of people per se, beyond the fact that there is a very inequitable allocation of land, hence affecting income, access to education, psychological well-being and overall life quality.

My work is mostly related to studying and analyzing the population and community dynamics of large mammals (elephants, ungulates); the interactions between animal species and with local human populations; the effects that some key ecosystem engineers such as elephants may have on the ecosystems. Mostly, these works contribute to enhancing our knowledge of the functional ecology of West African Sudanese savannas.

I am a Cameroonian zoologist active in small mammal research, with a focus on African bat zoogeography, ecology, systematics and conservation. I am member of various scienctific networks and societies (e.g. American Society of Mammalogy, African Bats, Bat Conservation Africa,and IUCN/SSC Bat Specialist Group).

I have conducted research on the effects of anthropogenic fires on Guinea savanna parklands of North of Ghana, West Africa in the last seven years. This is important because the North of Ghana reportedly contributes about 40% in the last 30 years of ecological fires in the Country. It is essential that we we ascertain and understand causes of fire, why people burn and consequence of the traditional uses of fire on the environment.

I observed in the study that fire applied in different landuses such as crop fields or farmlands for instance, affect woody species and soil differently from woodlands. It was also observed that controlled and prescribed burning affect woody species differently in protected areas from unprotected areas due to the different fire regime. Fire users in rural areas and protected areas have different reasons for applying fire. Thus, to understand people’s perception of and the practice of the use of fire, the survey revealed that fire practice are linked to livelihoods in rural areas of Africa These practices have influenced biodiversity in the Guinea savanna over a millennia but with little documentation on the impact of fire combined with land uses in the Sudano-Guinean savanna of West Africa.

I focus on bat research and conservation. I am interested in understanding the impacts of deforestation on bats. I have special interest in movement ecology of bats particularly in agro-environments. On conservation, my organization Batlife Ghana works with local communities to protect bat habitats and roost.

In my country where I work, deforestation is rather the norm than the exception. This tremendously affect certain species negatively, although some species take advantage of croplands. Areas where invasive plant species have taken over after deforestation are mostly avoided by most bats species.

How much biodiversity can we lose before it starts impacting our quality of life? We all depend on well-functioning ecosystems, whether we are aware of this or not. Yet measuring how much biodiversity we are losing across the African continent, and what that means for our well-being, is a difficult task. To address this challenge, we are mobilising hundreds of African biodiversity experts to produce a continental map of ‘biodiversity intactness’ that is credible and useful to African decision-makers.

My research project describes the factors influencing the coexistence of mesocarnivores under a large-predator-free scenario at Great Fish River Reserve and a Large predator scenario at Kwandwe Private Game Reserve, Eastern Cape, South Africa. Mechanisms behind ecological segregation will be assessed by combining results from camera-trapping, telemetry, and diet. Specific objectives are to (1) quantify home ranges sizes, distance movements, etc. (2) assess temporal segregation in activity patterns; and (3) evaluate diet segregation. This is important as it allows to describe the basic ecology of some mesocarnivore species for the first time, and secondly how trophic webs might or not be disrupted.

Although my answer to that is yes, I only have anecdotal evidence of that, since any specific study was developed in the area. Still, we have noticed a very high abundance of jackals (assessed through hundreds of field workdays and a 1-year survey of camera traps monitoring) at the Great Fish River Reserve (Eastern Cape, South Africa) due to the lack of large predators o control them. We know that dispersing jackals are leaving the reserve and tried to colonise surrounding areas including farms where they prey on livestock. This type of behaviour has been described across South Africa.

LinkedIn | ResearchGate | Twitter

Africa is home to over 80 species of small carnivores, and that most of them have not been studied thoroughly, or not studied at all, there is clearly a huge gap in our knowledge of small carnivores in particular, and ecosystem functioning in general. Hence, the launching of a first scientific study on the distribution, biology, ecology, behaviour and conservation of Libyan Striped Weasel in Africa, and more specifically in Tunisia, will certainly contribute toward filling a part, albeit small, of this gap, as well as enrich our general knowledge on African biodiversity.

According to Hayder and Do Linh San (in preparation), there is a decrease in both the occupancy and population size of Libyan Striped Weasels in Tunisia (as inferred from interviews of elderly local people and confirmation with field data), because the Libyan Striped Weasel is targeted by poachers and used commercially due to its medical virtues, and suffers from habitat loss and other threats. Therefore, studying the spatial and temporal dynamics of habitat use by species in semi-nature landscapes is a crucial first step towards conserving those species, since it allows us to understand their behaviour and ecological requirements, as well as determine their possible interactions with humans (conflicts and persecutions). Therefore, the present study will provide relevant information to develop effective conservation management plans for the Libyan Striped Weasel in North Africa.

LinkedIn | ResearchGate | Twitter

I study the ecology of plants, particularly forbs (i.e. ‘wildflowers’) in tropical and subtropical grasslands and savannas of southern Africa. Considering the rich forb flora in sub-Saharan Africa, their contribution to human well-being via a diverse suite of ecosystem functions and services remains understudied and, hence, underestimated. My research is therefore focused on patterns of forb species diversity and their functional responses to natural disturbances (e.g. herbivory and fire) and/or stressful events (e.g. drought) to better understand and predict the potential effects imposed by land-use intensification and climate change.

Studies on the potential impacts of human activities, land-use changes/intensification and climate change on the ecological integrity of African ecosystems are often biased towards vertebrates and certain plant groups. Forbs not only contribute substantially to the overall biodiversity of sub-Saharan Africa, but also provide important ecosystem functions (e.g. nutritious food items to both humans and livestock, medicinal resources etc.) and services (e.g. nutrient cycling, carbon sequestration, food security through supporting pollinators etc.) to human livelihoods. Anthropogenic pressures have pushed ecosystems into alternate stable states, which support lower forb diversity and a much weaker contribution to important ecosystem functions and services. Large-scale, intensive crop production has filtered out many species with the ability to store carbon belowground, which also serve as important medicinal plants for rural livelihoods in sub-Saharan grassy ecosystems. Intensive livestock grazing or the complete exclusion of large mammals and/or fire may deplete forb diversity and hence, negatively impact the stability of rangeland systems.

My research focuses on space use in large mammals and factors influencing it at various spatial scales, and integrates remote sensing with the more traditional field of behavioural ecology; with the aim of better understanding conservation in fragmented landscapes. I have a keen interest in direct and indirect herbivore-resources relationships and the integration of factors governing decisions at the small spatial scale through to landscape level, with particular attention to fragmented landscapes. Investigating the scales of resource use and selection within protected areas is fundamental in order to understand the long-term viability of herbivore populations, and to prevent the risk of local population extirpation.

I have been working in Tanzania since 2002 with a main focus into the biodiversity-rich forests of the Udzungwa Mountains where I helped establishing the Udzungwa Ecological Monitoring Centre in 2006 (http://www.udzungwacentre.org/). My research mainly focuses on understanding drivers of status and vulnerability of populations and communities, with most of my experience on mammals as the subject and camera trapping as the detection method.

One example is how increased deforestation induced by farming and livestock keeping in the valley adjacent to the forests impacted the connectivity of large mammals (elephants especially) but in turn carries the potential for increasing human-wildlife conflicts and loss of forest-based products to the people themselves.

My research interests lie within community ecology and ecosystem functioning. I am particularly interested in what drives animal distribution patterns, and how animals influence and shape ecosystems by means of herbivory and predation. Understanding these dynamics is imperative for the development of sound wildlife management practices and conservation strategies.

I studied the patterns of biodiversity in the Congo Basin rainforest and showed the effect of historical climatic changes on current species distributions.

https://www.seekingwilderness.be/

LinkedIn | ResearchGate | Twitter

I have worked mainly with the ecological consequences of predation, both through evaluating the effects of predation risk on the ecology of ungulates and by looking at the effects of an insectivorous diet on the ecology of small- and medium-sized carnivores.

I work on documenting amphibians in protected areas within the Central Congolian Lowland forests ecoregion in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with the goal of better understanding the little-known fauna of the Green Heart of Africa. Our effort contributes to the protection and conservation of Congolian biodiversity by informing the planning of wildlife managers.

I currently manage the Global Biodiversity Standard through BGCI. Prior to this I have worked mainly in coastal Kenya with conservation organizations, working to safeguard rare plants and develop capacity in botanical gardens to bring about conservation. I have conducted field work in highly threatened forest patches along the Kenyan Coast. The collections and surveys have shown incredible diversity persisting despite rapidly decreasing habitat.

The major impact that human activity and land use has had on the coastal flora has been loss of habitat. Burning for agriculture is one of the most directly visible as forest and individuals can be lost in moments. Logging pressure for timber and charcoal is also significant. The forests have been a key resource to local communities and this is now at a critical point of no return. This has led to the driving up of charcoal prices, loss of water towers and the traditional ways of life that go hand in had with intact forest.

https://www.biodiversitystandard.org

My work is mainly on biogeography, systematics and conservation of African small carnivores.

My work explores the origins and maintenance of frog diversity at multiple scales (genetic to community) in Central Africa. I am very interested in how climate change over since the Pleistocene has shaped contemporary diversity. This work can help inform conservation priorities in the face of human-driven climate change. My research program is museum and field based.

Large-scale monocultures like for growing of palm-oil can devastate frog communities. Such activities at centers of endemism (like in the Cameroon Volcanic Line), place many range-restricted species at risk of extinction.

https://gregjongsma.weebly.com/

Google Scholar | ResearchGate | Twitter

My primary research interests are the mechanisms by which ecosystems and species assemblages are maintained or modified. Impacts on biodiversity, necessarily, impact the composition and functioning of both ecosystems and more narrowly species assemblages. Consequently, without having insight into African biodiversity and how it responds to modification, it is impossible to understand how our systems function and what the likely impacts of future developments and impacts are likely to be.

My work in the Kalahari and the Karoo focuses on investigating the ecology of mesopredators in both modified and natural systems. Without a doubt, the presence of specific mesopredators on stock farms has an influence both on human activity and livelihoods. Predation on small stock influences the profitability of stock farms and leads to various modifications of human activity. Farmers alter their behaviour to try to prevent or at least mitigate against losses of stock to predation. On a broader level, although predation is one of a number of stressors on small stock farmers, the reduced profitability of small stock farming as a consequence of such stressors has to lead to a reduction in the number of stock farming enterprises, farmers altering their management focus to a more diversified stocking/management strategy that includes lower densities of small stock and more wild animals. In the extreme, farmers have abandoned their farms and moved to more urban areas or they have decided to move to different areas and pursue farming of a different nature.

Dr Hanneline Smit-Robinson heads up BirdLife South Africa’s Conservation Division. She is a senior manager and biodiversity conservation specialist. Her key responsibilities, as Head of Conservation, include oversight of all BirdLife South Africa’s Conservation Programmes, including seabird, landbird and habitat conservation, policy and advocacy engagement, regional support to BirdLife partners throughout Africa, community conservation and avitourism projects.

I am a carnivore conservation biologist by training and am the Chair of the Wild Dog Advisory Group, South Africa. These days I mostly focus on providing strategic direction and oversight to a wide range of projects run by the Endangered Wildlife Trust across southern and parts of East Africa. Our work aims to reduce human impacts on threatened species and habitats in ways that bring benefits to both people and nature. I love working with teams to design new projects and create ways to deliver cost-effective and sustained impact.

In South Africa, private (and increasingly, communal) wildlife ranching has a really significant influence – sometimes positive, other times negative – on the distribution and abundance of a range of wildlife species. The trick is to find ways to maximize the biodiversity benefits of wildlife ranching, while removing some of its adverse effects (think intensive management), and ensuring that economic benefits are socially equitable.

LinkedIn | ResearchGate | Twitter

It is important to promote conservation especially this time when population is increasing and thus increasing human wildlife conflicts, leads to biodiversity loss and negatively impact conservation. In my study area, there are alot of changes especially habitat loss and habitat alteration which have led to reduction in species of various kinds.

I work as a herpetologist and ecological consultant, and have performed research widely across the Afrotropical region. I maintain a strong connection to the scientific and conservation communities and have contributed to conservation assessments and publications, and species conservation and prioritization workshops.

https://www.harveyecological.co.za/

He is a conservation ecologist and a faculty member in the School of Natural Resource Management, Nelson Mandela University based on the George Campus. His research focuses on large terrestrial mammal ecology but he also occasionally works on birds, reptiles and other interesting wild animals. He completed his undergraduate studies and Masters degree at University of South Africa and Nelson Mandela University, and his PhD at University of Kwazulu-Natal. He tries, through his research and collaboration networks, to contribute to the conservation of Africa’s unique biodiversity and landscapes.

https://wildecolabdotcom.wordpress.com/

I am a Post-Doctoral Fellow affiliated with the Centre for Functional Biodiversity at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. I am interested in mammal ecology, human-wildlife conflicts, and prey-predator interactions, particularly for small carnivores. My previous research identified and quantified the impacts of several anthropogenic pressures on the ecology of three solitary mongooses. We identified and highlighted their behavioural adaptability and flexibility to land-use change. My current research investigates the drivers of anthropogenic pressures and landscape features on terrestrial mammal species richness, distribution, and occupancy in the KZN Midlands and within the Protected National game parks of northern Zululand.

The anthropogenic transformation of natural habitats, whether for agricultural or urban expansion, is a threat to biodiversity. Generalist species are often more adaptable than expected to broad anthropogenic pressures and can exploit the unique and unoccupied niche. Understanding whether small mammalian carnivores respond positively or negatively to these human-induced changes is paramount for developing best-practice management strategies in these dynamic systems.

My research has focused on behavioural ecology and social dynamics of banded mongooses in Uganda. With a focus on demography, and understanding factors affecting survival and distribution of reproductive success, alongside impacts of human waste food availability on spatial use and behaviour, I have an appreciation of within species (and group) behaviour and ecology, and interactions with environment and other species. I also have some experience with chimpanzee social ecology from Uganda. My research on grey mouse lemurs in Madagascar was similarly concerned with social dynamics, and the costs and benefits of sociality (communal creching). In addition, in Madagascar, I studied the behavioural ecology of social spitting spiders. In South Africa, I conducted stress physiology research on a diversity of African ungulates, to better understand how capture (for transport/conservation intervention) experience impacts individual animals. Combined, I have an overview of mammal dynamics within and across a diversity of ecosystems, and an insight into the behaviour, physiology, and ecology of species. Biodiversity depends upon ecological interactions, and effective biodiversity conservation depends upon understanding the dynamics of species within ecosystems, and their interactions and interdependencies.

The influence of people on ecosystems and the species that inhabit them is pervasive. Some species are impacted directly, others indirectly, with some areas/habitats more heavily influenced by people than others. The response of individual species is determined by the human influence (threat?) and the ecology (natural history) of the species present. In Uganda, I observed the direct influence of poor waste disposal on the natural ecology of species (in particular the banded mongoose). Movements, interactions, and behaviour were influenced by the attraction of ‘free’ food at waste disposal sites. Where animals become habituated to humans by the presence of food, human-wildlife conflicts tend to arise. In Madagascar, deforestation and resource extraction are very direct threats to species survival, e.g. lemurs, some species of which are highly restricted. If we remove habitat, we remove the species that live in and depend upon those habitats. As habitats decline, populations reduce and become more vulnerable to the negative influences of disease, demographic and genetics. Biodiversity ultimately provides livelihoods for people. When we lose the forest, we lost its value, in terms of renewable resource extraction, ecotourism potential, and increase risk of zoonotic disease transfer between human and wildlife populations. Like or dislike it, in South Africa, the large mammal community has value via trophy hunting. Much wild land, that would otherwise be devoted to traditional or intensive agriculture, is given to ‘wildlife ranching’, and therefore supports managed communities of large mammals. Given the fencing of such areas, large mammals need to be actively captured and translocated, to enable colonisation of new sites, and to refresh gene pools. Capture and translocation has direct impacts on the individual animals, and to the source and target populations, and ultimately, influences human values and management of the land, for trophy, meat (biltong), and tourism. As an industry, the implications of wildlife management for human economic and welfare are particularly complex and emotive here.

https://www.jasongilchrist.co.uk/

My research is predominantly focused on global change in South African terrestrial ecosystems and revolves around field studies and spatial data analyses with the goal of informing policy and management. Most of my projects focus on fire, water, land cover (including invasive species) and climate change, predominatly in the Greater Cape Floristic Region. My core aims are to improve our understanding of:

– the processes that determine the structure, composition, and function of ecosystems

– how global change drivers are altering these processes

– and subsequently ecosystems

– how ecosystems function and the implications of global change for societal benefits

– how we monitor and mitigate or adapt to these impacts

Systematics, conservation and evolution of African bats

My work is mainly systematics and evolution, describing several new taxa always among bats.

Equatorial Guinea economy is shifting from moderate use of the forest as a source of traditional goods, food, local timber, small-scale crops into highly impacting activities that are causing rapid forest degradation and an evident loss of biodiversity. Nevertheless, the situation can be reversed yet.

My field research has taken me to Central America, the Caribbean, and eight African countries. After observing African monkeys in a diverse range of habitats I became fascinated by their widespread presence and behavioural flexibility around the complex relationships primates and people have with one another. I am committed to partnering with local communities and leaders to support their priorities in preserving African biodiversity.

Being able to work in different parts of Africa has been eye-opening for me in learning more about the human activities and land use that most affect primates. Where I currently work in West Africa, deforestation is a major threat to primate conservation and human communities.

Our research focuses on the ecology of galagos in Kinshasa. This work consists on one hand identification of the sites of occurrence of galagos in Kinshasa and on the other hand in studying their ecology in these environments dominated by strong anthropic pressure. We managed to report the presence of galagos in the urban forests of Kinshasa while everyone thought they were absent due to the strong and rapid urbanization of this city.

The city of Kinshasa faces a rapid and often uncontrolled urbanization which causes the destruction of forests for the construction of housing or by the use for various needs (firewood, agriculture, livestock) which leads to the loss of biodiversity. This uncontrolled urbanization does not always guarantee the well-being of men since it is at the base of most of the land erosion that the city of Kinshasa is experiencing today.

Understanding if and how tropical forests can adapt to a changing climate is pivotal to our understanding of anthropogenic impacts on the ecosystem. I take a functional traits approach to disentangle how tropical forests in West Africa have shifted their trait composition through time as an adaptation to a changing environment.

Increasing land use change from forest to cocoa plantation and illegal logging have increased the fragmentation of forests and likely caused a decrease in their species and functional trait composition across the last decades.

https://www.jesusaguirre-spatialecology.com

https://www.eci.ox.ac.uk/people/jaguirregutierrez.html

I study the savanna ecosystems of southern and eastern Africa, with a particular interest in understanding trophic interactions among large mammals and the nutrient flows they mediate.

Large mammals in African savannas are particularly susceptible to being killed by humans and to losing habitat due to human land use. Generally, the well-being of local people is diminishing in areas where wildlife resources are declining, due to foregone opportunities for sustainable use.

My work mainly focuses on understanding who lives where and why? Starting from ground surveys and taxonomic identification to ecological requirements of individual species and overarching biogeographical questions with the main aim to provide relevant data for urgently required conservation actions.

Work from colleagues in West Africa and other regions in the world indicate that consumption of frogs could lead to an increase in mosquito transmitted diseases because the tadpoles of some species feed on mosquito larvae. Establishing a system where frogs can be used sustainably and with benefits for humans and nature would be an excellent step forward.

John Measey is an invasion scientist who works on reptiles and amphibians notably in southern Africa.

Invasive species, especially woody plants, are impacting increasingly larger areas of land, including reserves. These impact amphibians and reptiles by altering the thermal regime and increasing the intensity and frequency of natural fires.

Jonathan is documenting the distribution and ecology of the Fox’s Weaver Uganda’s only endemic bird species and the Karamoja Apalis an East African endemic in North-eastern Uganda. His research is playing a huge role in identifying key habitats for the conservation of two globally threatened species in North-eastern Uganda, this information forms the basis of NatureUganda’s Conservation focus and actions in the region.

Grasslands were once the most widespread vegetation type in Uganda,however, large swaths of grassland have been converted into farmland and settlements, the only intact grasslands are now restricted within National Parks and Wildlife Reserves. The reduction in the size of grasslands has mostly impacted large ranging raptors such as the Martial Eagle, Bateleur and Secretary Bird. The Karamoja and Iteso of North-eastern Uganda are cattle keepers whose life revolves around their livestock, the reduction in grasslands has led to reduced pasture for their animals. The Nomadic way of life of the Karimojong for example will soon not be possible due to fragmentation of grassland habitats in the region. Without the seasonal movements especially during the dry season, to areas with good pastures the health of their cattle and subsequently their own wellbeing will be in jeopardy.

LinkedIn | ResearchGate | Twitter

I’ve contributed to delineating birds and mammals distribution in SE Senegal, a region with a lack of biodiversity inventories, therefore improving knowledge about species’ conservation status and adding natural value to the territory.

Fruits of the vine Saba senegalensis is a sought-after resource by people, but also by chimpanzees. Sometimes conflict arises, and chimpanzees have to avoid humans by changing their favourite areas or shifting to alternative food.

Extensive camera trapping has been very helpful to complete mammal inventories in remote areas. But for birds, which appear frequently in the videos, cameras have also shown unexpected behaviours and even species unnoticed with conventional ornithological methods. Camera trapping is not usually acknowledged as a bird-research tool, but in some circumstances it can provide interesting insights into communities and species’ ecology.

My work focuses on phylogeography, biogeography, taxonomy, speciation, species concepts, host-parasite co-evolution, biodiversity distribution – in all subjects the African small mammals (rodents, shrews, sengis, etc.) are used as main research models.

We are primarily working in relatively undisturbed areas. However, sometimes we have worked in agricultural regions and we realized that intensive farming and overgrazing significantly reduces biodiversity of small terrestrial mammals. This is observable everywhere, but probably the worst situation is in some Ethiopian regions (especially overgrazing can be a problem for unique fauna of Ethiopian highlands).

For my PhD, I studied the effects of land cover and anthropogenic change on bats’ activity, microbiome, and viral prevalence in northeast Eswatini in collaboration with Prof. Ara Monadjem (University of Eswatini). We made the first record of the Midas free-tailed bat (Mops midas) for Eswatini and the first record of Streblidae bat ectoparasites for Eswatini, along with a review of the status of the ectoparasite genus Raymondia across Africa. I have also collaborated with UnEswa students on studies quantifying the effects of land use on small mammals and birds. As a member of the IUCN Bat Specialist Group, I have authored or co-authored five RedList species accounts for African bats and participated in drafting the IUCN Guidelines and Recommendations to Prevent the Transmission of Covid-19 from Humans to Bats.

Northeast Eswatini is a mosaic of savanna, sugarcane plantations, and rural villages. To understand how these land-cover types affect bats, we measured the activity levels of different types of bats based on how they forage (aerial, edge, and clutter foragers) across the landscape. We found that each type of bat responded to different landscape attributes at different spatial scales. Aerial bats responded positively to savanna fragmentation, especially within sugarcane plantations, edge bats responded to reduced shrub cover and shorter distance to water, and clutter activity was most influenced by water availability in the landscape. This means that maximizing the number of remnant savanna fragments in sugarcane plantations and villages, reducing shrub encroachment, and preserving both natural and artificial water sources can promote the activity of different types of bats across this landscape potentially allowing them to provide important people with ecosystem services such as insect pest control.

Google Scholar | LinkedIn | ResearchGate | Twitter

I am interested in scaling up Ecological Restoration – with a focus on how to recover/re-introduce native biodiversity to damaged/degraded systems (so that Nature’s Contributions to People are optimised while also recovering biodiversity). Visualising how biodiversity has been impacted on the continent (e.g. through the BII) is a key research/planning opportunity.

Invasive plants, especially where they dominate, certainly impact native species diversity and abundance; these species also result in feedbacks to human well-being (e.g. allergies; fire risk; hydrological risk and the list goes on). Likewise, restorative efforts on the landscape could shift these impacts and feedbacks.

My doctorate thesis was about how an island primate, the endangered Zanzibar red colobus monkey, is behaviorally adapting to human-driven change in coastal forests. My team and I helped stop golf course development and trash dumping by hotels in a forest that became a new protected area, the Kiwengwa-Pongwe Forest Reserve. We published articles about mangrove use by Zanzibar red colobus and a book, Primates in Flooded Habitats. In 2008, I co-founded a project that is now the Southern Tanzania Elephant Program that fosters human-elephant coexistence. From 2013-2016, I researched risk and cognition in samango monkeys at two Afromontane forest sites in South Africa finding observer effects on monkeys’ landscape of fear.

In Zanzibar, I witnessed the loss of native coral rag forest and tree species for agriculture, building poles, and plantations of Casuarina; this forest loss is associated with the loss of native biodiversity and loss of medicinal plants for local people. Forest loss also increases contact between people, domestic animals such as dogs and cattle and wildlife. I witnessed dog packs harassing monkeys and duiker in forests in Zanzibar even in fringe mangroves at the tip of Uzi Island where terra firma forest directly adjacent to mangrove was being cleared for agriculture. I also observed adult red colobus grooming a calf beyond the forest margin. In the Udzungwa Mountains, polyspecific primate associations appear to be more common at forest edges than in forest core and this may have implications for disease emergence and for human-wildlife conflict. Where there is a lack of a buffer zone between intact forest and farms, and a lack of connectivity between forested areas, large mammals such as elephants, bushpigs, and baboons easily enter farms for crop-use; mitigation is that much more challenging in areas without buffer zones. For example, where we used a beehive fence to deter elephants from farmers’ crops, the fence had to be placed in a certain way at the periphery of the Udzungwa Mountains National Park so that bees would not pose a risk to farmers at work in their nearby fields. In Hogsback, South Africa, collaborators and I recommended the removal of acorns (from oaks planted by Europeans) from gardens so that these would not attract groups of samango monkeys that ingest the acorns during winter. The monkeys are perceived by some people as a nuisance when they enter gardens; the acorns are also detrimental to monkeys’ dental health. In Canada, in areas previously mined and therefore containing webs of roads, human (often with dogs) access for recreation is frequent and mammals such as mountain goats move at night possibly to avoid people. We saw this with elephants in Udzungwa, where movement and use of crops occurs at night when farmers are not in their fields. Coexistence between people and other animals will continue to pose a challenge especially where land planning excludes local people and their knowledge or fails to consider the landscape at large or species interactions.

http://www.conservationkat.com/

I am a herpetologist whose research explores the morphology, biodiversity, and evolution of amphibians and reptiles, with a regional specialization in central Africa and a taxonomic focus on snakes and snakebite. My team carries out field-based and collections-based research, contributing to a strong herpetological foundation on which both biodiversity conservation and snakebite management initiatives can build.

Expansion of human populations into biodiverse ecosystems brings humans into contact with wildlife, including snakes. Snakebite is a neglected public health problem in central Africa, and one which can only be expected to worsen with anthropisation of habitats. At the same time, conservation of snakes and the ecosystems they are part of, is impacted by some of the same global forces.

Researches Perennial African rangeland grasses for Ecological Restoration

Land fragmentation and conversion of natural grassy biomes (rangelands) for agricultural production is a major land use influencing plant biodiversity and partly contributing to rangeland degradation due to reduced perennial vegetation cover.

Google Scholar | Twitter | LinkedIn

https://www.uu.nl/staff/KZMganga

My main research interests are in evolutionary systematics and ecology of African small mammals, mainly rodents (taxonomy, phylogeny, phylogeography, community ecology, population biology). My main skills concern:

i) sampling methods for small mammal inventories, community ecology and population surveys;

ii) integrative taxonomy combining morphological, molecular and chromosomal analyses.

Besides long-term studies in (mainly African) rodent systematics, phylogeny and phylogeography, I have been involved in projects on African small mammal ecology in various contexts (fault and gallery forest biodiversity in southern Mali, gold-mining areas in southeastern Senegal, agroecosystems of North Senegal) with a recent focus on invasive species and zoonotic processes.

https://www6.montpellier.inrae.fr/

My research interests primarily include terrestrial ecology of large mammals, with a focus on Carnivore Ecology, Human-Wildlife Conflict and Predator-Prey Interactions. I am broadly interested in the drivers of both predator and prey communities in terrestrial ecosystems. Specifically, I am interested in the top-down (e.g., predation, diseases, human impacts) and bottom-up (e.g., rainfall, nutrients, habitat characteristics) mechanisms structuring carnivore and prey communities and variation in these processes between nature reserves and anthropogenically modified systems.

Most of my work has been conducted in the extensive livestock grazing areas in the Karoo, South Africa. Arguably, this land use has fewer negative impacts on ecosystems compared to cropping or urbanization, for example. However, in some cases farmers overgraze rangelands leading to several knock-on effects related to ecosystem functioning. In addition, the lethal management of carnivores perceived to cause livestock mortality is also impacting ecosystem structure and functioning.

My research focus on carnivore ecosystem services, disservices and conservation ecology, especially in production landscapes. Quantifying the role of predators in production ecosystems remains key for long term sustainability.

Large scale bush clearing, as well as unsustainable resource extraction, reduce habitat available for predators. Lower habitat availability leads to declines in predator abundance and diversity, lowering resilience and functional redundancy. These combined effects inadvertently leads to reduced ecosystem services like bio-control of pests and seed dispersal. Reduced predation on rodent pests for example, leads to lower crop yield and higher seed contamination – all affecting food security.

I perform herpetofauna surveys across Africa, mostly as part of EIAs for proposed developments. I use this data and experience to help inform research and conservation efforts on African herpetofauna.

http://www.enviro-insight.co.za/

I am interested in plant diversity in Angola and the environmental factors that shape vegetation, with a particular interest in frost and fire.

It is always assumed that fire is a natural factor in all African grassland ecosystems. However, at least the timing of fires is nowadays controlled by people who use fire with different objectives for land use. To disentangle the seasonal effects of fire, we have installed systematic fire experiments in three openland ecosystems in central Angola to investigate the influence of different fire timings on functional types such as grasses, geoxyles, and trees. For this, we measure changes in species composition and cover, as well as response variables such as the number of inflorescences of grasses, and leaf or shoot length of dicotyledonous plants. Results may help local stakeholders to better manage species rich tropical grasslands in terms of biodiversity conservation.

The Institute for Communities and Wildlife in Africa has been surveying African biodiversity to understand the potential impacts of different land use on wildlife and how abundance may influence negative interactions between humans and wildlife. We have projects throughout southern Africa on large and medium sized carnivores in addition to research on primates focussing primarily on baboons. Our single greatest contribution to biodiversity monitoring has been in the drylands of South Africa (Karoo) where we have sampled mammalian species richness both at a regional and local scale.