Have worked on African carnivores in the wild since 31 years for PhD and post-doc research in South Africa, Namibia, Swaziland (aardwolf, black-footed cat, African wildcat, arid habitat mongoose, mustelids, canids), a for 5 years in the Moroccan Sahara (sand cat, canids, mustelids). As a curator of two scientifically led zoos in the past 23 years I also facilitate and perform research on captive carnivores, particularly intensively for the felids (IUCN Cat SG member) and link to in-situ projects.

It has a profound impact, particularly for human-wildlife conflict species (black-backed jackal, caracal, leopard – collateral damage to smaller carnivores like black-footed cat, African wildcat, Cape fox) through indiscriminate control measures by the farming community. Overgrazing, encroachment, disturbance, termite control, direct persecution. Also the association of domestic carnivores (feral and shepherding dogs, domestic cats) with human presence – impact via disease transfer and also predation/killing.

I am a behavioural ecologist specialising in the behaviour of small carnivores such as yellow mongoose, bat-eared foxes, and black-backed jackal. My past research includes work on social primates and whistling rats. I am very interested in decision-making as affected by different types of risk, which includes the interaction between humans and small carnivores. Anthropogenic habitats pose both risks and rewards to small carnivores, while increased interspecific contact may also expose humans to more zoonotic pathogens. To uncover patterns of small-carnivore behaviour at a larger scale, I am currently engaging in more collaborative research across study sites and species.

Very often, small carnivores do well in disturbed habitats, where their social behaviour may increase. Although this social (and dietary) flexibility is not detrimental to the small carnivores per se, it does tend to increase the circulation of pathogens in their populations, and by extension also exposes humans to more risk from the zoonotic disease.

I worked on aardvarks many years ago and am currently Chair of the IUCN Afrotheria Specialist Group.

There is evidence (not from my own work though) of climate change impacting aardvarks in very dry areas like the Kalahari.

I have spent more than a decade studying African pangolins, during which time I have been privileged to travel widely in Africa, and have seen three of the four African pangolin species in the wild. In addition to my pangolin-related work, I have also done several surveys of amphibians, reptiles and birds in southern, Central and West Africa.

I am a wildlife biologist specialising in the natural history, ecology and conservation of small carnivores. I am particularly interested in their spatial ecology, activity rhythms, diet and social organization. The acquired knowledge allows us to better understand niche partitioning and the potential impacts of top-down and bottom-up processes on these species, and conversely their potential impact on their predators and prey. Ultimately, a better understanding of both species natural history and ecological processes may help identify conservation needs and devise conservation actions.

I have so far mostly worked in Protected Areas (PAs), focusing on otherwise quite flexible small mammal species. Despite noticing drastic habitat differences between PAs and e.g. neighbouring livestock farms, most of the studied species are still present there, sometimes likely at similar densities. In some cases, the absence of medium-size predators may even favour the smaller carnivore species. It is also well-known that some generalist rodent species thrive in cropland areas, whereas specialists tend to be extirpated. I did not have the “opportunity” to observe the impact of human activities on the well-being of people per se, beyond the fact that there is a very inequitable allocation of land, hence affecting income, access to education, psychological well-being and overall life quality.

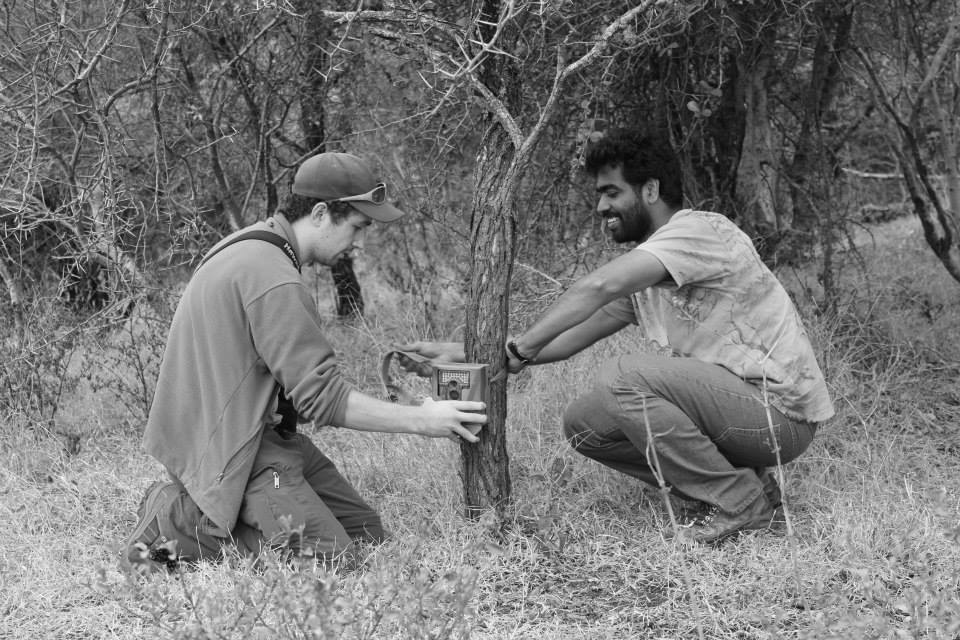

My research project describes the factors influencing the coexistence of mesocarnivores under a large-predator-free scenario at Great Fish River Reserve and a Large predator scenario at Kwandwe Private Game Reserve, Eastern Cape, South Africa. Mechanisms behind ecological segregation will be assessed by combining results from camera-trapping, telemetry, and diet. Specific objectives are to (1) quantify home ranges sizes, distance movements, etc. (2) assess temporal segregation in activity patterns; and (3) evaluate diet segregation. This is important as it allows to describe the basic ecology of some mesocarnivore species for the first time, and secondly how trophic webs might or not be disrupted.

Although my answer to that is yes, I only have anecdotal evidence of that, since any specific study was developed in the area. Still, we have noticed a very high abundance of jackals (assessed through hundreds of field workdays and a 1-year survey of camera traps monitoring) at the Great Fish River Reserve (Eastern Cape, South Africa) due to the lack of large predators o control them. We know that dispersing jackals are leaving the reserve and tried to colonise surrounding areas including farms where they prey on livestock. This type of behaviour has been described across South Africa.

LinkedIn | ResearchGate | Twitter

Africa is home to over 80 species of small carnivores, and that most of them have not been studied thoroughly, or not studied at all, there is clearly a huge gap in our knowledge of small carnivores in particular, and ecosystem functioning in general. Hence, the launching of a first scientific study on the distribution, biology, ecology, behaviour and conservation of Libyan Striped Weasel in Africa, and more specifically in Tunisia, will certainly contribute toward filling a part, albeit small, of this gap, as well as enrich our general knowledge on African biodiversity.

According to Hayder and Do Linh San (in preparation), there is a decrease in both the occupancy and population size of Libyan Striped Weasels in Tunisia (as inferred from interviews of elderly local people and confirmation with field data), because the Libyan Striped Weasel is targeted by poachers and used commercially due to its medical virtues, and suffers from habitat loss and other threats. Therefore, studying the spatial and temporal dynamics of habitat use by species in semi-nature landscapes is a crucial first step towards conserving those species, since it allows us to understand their behaviour and ecological requirements, as well as determine their possible interactions with humans (conflicts and persecutions). Therefore, the present study will provide relevant information to develop effective conservation management plans for the Libyan Striped Weasel in North Africa.

LinkedIn | ResearchGate | Twitter

I have been working in Tanzania since 2002 with a main focus into the biodiversity-rich forests of the Udzungwa Mountains where I helped establishing the Udzungwa Ecological Monitoring Centre in 2006 (http://www.udzungwacentre.org/). My research mainly focuses on understanding drivers of status and vulnerability of populations and communities, with most of my experience on mammals as the subject and camera trapping as the detection method.

One example is how increased deforestation induced by farming and livestock keeping in the valley adjacent to the forests impacted the connectivity of large mammals (elephants especially) but in turn carries the potential for increasing human-wildlife conflicts and loss of forest-based products to the people themselves.

I have worked mainly with the ecological consequences of predation, both through evaluating the effects of predation risk on the ecology of ungulates and by looking at the effects of an insectivorous diet on the ecology of small- and medium-sized carnivores.

My work is mainly on biogeography, systematics and conservation of African small carnivores.

My primary research interests are the mechanisms by which ecosystems and species assemblages are maintained or modified. Impacts on biodiversity, necessarily, impact the composition and functioning of both ecosystems and more narrowly species assemblages. Consequently, without having insight into African biodiversity and how it responds to modification, it is impossible to understand how our systems function and what the likely impacts of future developments and impacts are likely to be.

My work in the Kalahari and the Karoo focuses on investigating the ecology of mesopredators in both modified and natural systems. Without a doubt, the presence of specific mesopredators on stock farms has an influence both on human activity and livelihoods. Predation on small stock influences the profitability of stock farms and leads to various modifications of human activity. Farmers alter their behaviour to try to prevent or at least mitigate against losses of stock to predation. On a broader level, although predation is one of a number of stressors on small stock farmers, the reduced profitability of small stock farming as a consequence of such stressors has to lead to a reduction in the number of stock farming enterprises, farmers altering their management focus to a more diversified stocking/management strategy that includes lower densities of small stock and more wild animals. In the extreme, farmers have abandoned their farms and moved to more urban areas or they have decided to move to different areas and pursue farming of a different nature.

My research has focused on behavioural ecology and social dynamics of banded mongooses in Uganda. With a focus on demography, and understanding factors affecting survival and distribution of reproductive success, alongside impacts of human waste food availability on spatial use and behaviour, I have an appreciation of within species (and group) behaviour and ecology, and interactions with environment and other species. I also have some experience with chimpanzee social ecology from Uganda. My research on grey mouse lemurs in Madagascar was similarly concerned with social dynamics, and the costs and benefits of sociality (communal creching). In addition, in Madagascar, I studied the behavioural ecology of social spitting spiders. In South Africa, I conducted stress physiology research on a diversity of African ungulates, to better understand how capture (for transport/conservation intervention) experience impacts individual animals. Combined, I have an overview of mammal dynamics within and across a diversity of ecosystems, and an insight into the behaviour, physiology, and ecology of species. Biodiversity depends upon ecological interactions, and effective biodiversity conservation depends upon understanding the dynamics of species within ecosystems, and their interactions and interdependencies.

The influence of people on ecosystems and the species that inhabit them is pervasive. Some species are impacted directly, others indirectly, with some areas/habitats more heavily influenced by people than others. The response of individual species is determined by the human influence (threat?) and the ecology (natural history) of the species present. In Uganda, I observed the direct influence of poor waste disposal on the natural ecology of species (in particular the banded mongoose). Movements, interactions, and behaviour were influenced by the attraction of ‘free’ food at waste disposal sites. Where animals become habituated to humans by the presence of food, human-wildlife conflicts tend to arise. In Madagascar, deforestation and resource extraction are very direct threats to species survival, e.g. lemurs, some species of which are highly restricted. If we remove habitat, we remove the species that live in and depend upon those habitats. As habitats decline, populations reduce and become more vulnerable to the negative influences of disease, demographic and genetics. Biodiversity ultimately provides livelihoods for people. When we lose the forest, we lost its value, in terms of renewable resource extraction, ecotourism potential, and increase risk of zoonotic disease transfer between human and wildlife populations. Like or dislike it, in South Africa, the large mammal community has value via trophy hunting. Much wild land, that would otherwise be devoted to traditional or intensive agriculture, is given to ‘wildlife ranching’, and therefore supports managed communities of large mammals. Given the fencing of such areas, large mammals need to be actively captured and translocated, to enable colonisation of new sites, and to refresh gene pools. Capture and translocation has direct impacts on the individual animals, and to the source and target populations, and ultimately, influences human values and management of the land, for trophy, meat (biltong), and tourism. As an industry, the implications of wildlife management for human economic and welfare are particularly complex and emotive here.

https://www.jasongilchrist.co.uk/

I’ve contributed to delineating birds and mammals distribution in SE Senegal, a region with a lack of biodiversity inventories, therefore improving knowledge about species’ conservation status and adding natural value to the territory.

Fruits of the vine Saba senegalensis is a sought-after resource by people, but also by chimpanzees. Sometimes conflict arises, and chimpanzees have to avoid humans by changing their favourite areas or shifting to alternative food.

My research interests primarily include terrestrial ecology of large mammals, with a focus on Carnivore Ecology, Human-Wildlife Conflict and Predator-Prey Interactions. I am broadly interested in the drivers of both predator and prey communities in terrestrial ecosystems. Specifically, I am interested in the top-down (e.g., predation, diseases, human impacts) and bottom-up (e.g., rainfall, nutrients, habitat characteristics) mechanisms structuring carnivore and prey communities and variation in these processes between nature reserves and anthropogenically modified systems.

Most of my work has been conducted in the extensive livestock grazing areas in the Karoo, South Africa. Arguably, this land use has fewer negative impacts on ecosystems compared to cropping or urbanization, for example. However, in some cases farmers overgraze rangelands leading to several knock-on effects related to ecosystem functioning. In addition, the lethal management of carnivores perceived to cause livestock mortality is also impacting ecosystem structure and functioning.

My research focus on carnivore ecosystem services, disservices and conservation ecology, especially in production landscapes. Quantifying the role of predators in production ecosystems remains key for long term sustainability.

Large scale bush clearing, as well as unsustainable resource extraction, reduce habitat available for predators. Lower habitat availability leads to declines in predator abundance and diversity, lowering resilience and functional redundancy. These combined effects inadvertently leads to reduced ecosystem services like bio-control of pests and seed dispersal. Reduced predation on rodent pests for example, leads to lower crop yield and higher seed contamination – all affecting food security.

I have been surveying African biodiversity, first in southern Africa to understand the potential impacts of extensive small-livestock farming and protected area on wildlife and the factors influencing people-wildlife interactions. I now work in West Africa on wildcats, notably leopards and African golden cats, with the aim of developing regional conservation strategies.

In arid rangelands in South Africa, we highlighted that species richness was as high as in adjacent protected areas, although large carnivores were absent. Some species like caracals can even thrive on farmlands, due to the absence of larger competitors and the abundance of human-produced foods in the form of sheep. Negative interactions with farmers are common as caracals can prey on livestock.

I have a wide interest in the conservation field, from studies on small mammals and carnivores to the connections people experience in nature and the role protected areas can play in the well-being of people. My role as a regional ecologist for the Cape Parks is exciting as you are working at the interface between science and management. The Cape National Parks provide the opportunity to work in diverse habitats and ecosystems where I am responsible for co-ordinating, conducting and reporting on aerial surveys of the wildlife species and wildlife management recommendations in these parks.

I work on the applied ecology of large carnivores in Africa. This is to better understand them and help improve their conservation.

I have noticed a decline in the quality of South Africa’s rivers and other fresh water bodies since I started working on otters in 1993. This has had a negative effect on water provisioning in South Africa and so affects everyone.

LinkedIn | ResearchGate | Twitter

https://www.michaelsomers.co.za/

Prof. Morgan Hauptfleisch holds a BSc. Honours degree in Ecology and Botany, an MSc. in Plant Ecology and Wildlife Management and a PhD in Environmental Management. He is principal of the Biodiversity Research Centre at the Namibia University of Science and Technology. He lectures in Ecology, Rangeland and Wildlife Management and Natural Resource Management and is currently involved in research on the topics of environmental impact assessment, human wildlife conflict, wildlife census and sustainable wildlife management. He has authored numerous journal papers, book chapters and popular articles on these subjects based on research in six African countries. He serves on the board of the Southern African Institute for Environmental Assessment and the council of the Namibia Chamber of Environment. He also serves on the editorial committee of the Namibian Journal of Environment. His major research collaborators include the University of St. Andrews (UK), Dartmouth College (USA), Potsdam University (Germany), UCT (RSA) and North-west University (RSA).

One of his priority research areas concerns multiple land-use systems and the movement of wildlife between different land-uses as well as mammal species density and diversity on conservation, agriculture and mixed land use. The research includes the movement of wildlife between parks and neighbours, and the effect thereof on livelihoods and ecosystem services. This highlights barriers to movement and effects such as human-wildlife conflict and poaching risk. Namibia’s communal conservancy programme is known for its successes in terms of bolstering rural livelihoods from consumptive and non-consumptive wildlife use and protecting endangered large mammal species on extensive and fence-free natural lands. His current research seeks to understand how wildlife moves within this system and well on the interface with national parks and intensively-fenced commercial farmland on its borders. This work is done in collaboration with many Namibian and international conservation and academic partners, such as Giraffe Conservation Foundation, the Namibian Chamber of Environment, the Namibian Ministry of Environment Forestry and Tourism, Potsdam University, University of St. Andrews, the Cologne Zoo and black-footed cat working group. As founder and lead of the NUST Biodiversity Research Centre, he supervises Master and PhD students within the research areas above as well as applied topics relating to wildlife conservation and management in Namibia and beyond.

Contrary to much of the rest of Africa, Namibia has a low human population density, and has more than doubled its protected area network over the past 15 years. This has had a positive effect on wildlife populations, however it has increased human-wildlife conflict. The extent of this conflict has had socio-economic and political implications. There is therefore current pressure to reduce populations of especially large carnivores. Retaliatory persecution of carnivores is prevalent, but also often indiscriminate through the use of poisons and gin traps at a concerning scale. Since livestock farming dominates much of the freehold land, climate change, overgrazing and bush encroachment are reducing rangeland productivity, with a likely impact on small carnivores and their prey.

Nico Avenant’s observations made during his post-graduate studies, museum collection trips and involvement with environmental impact assessments, led to his current research field, i.e. small mammal community characteristics as indicators of habitat integrity. For this, he has worked in a large diversity of habitats, in different management areas (including formal nature reserves and other protected areas, conservancies, wetlands, pans, game farms, commercial stock and crop farms, subsistence farming areas, coastlines, open-cast mines, an army training base and a botanical garden), in the different countries South Africa, Lesotho, Eswatini, Namibia, Malawi and Cambodia, and on Sub-Antarctic Marion Island.

I have been working for more than 20 years on the systematics, evolution, biogeography, molecular ecology and conservation of small Carnivores (especially viverrids: genets, civets, linsangs) and Pangolins.

I am a conservation scientist at Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History (SACON), India and an Honorary Research Fellow at the Centre for Functional Biodiversity, School of Life Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. I am interested in large and meso-carnivore ecology, human-wildlife interaction and prey-predator interactions. My research identified wetland patches key for the survival of wetland-dependent species in fragmented landscapes, unique habitats that support intact mammal assemblages and how large carnivore populations are vulnerable to extinction, in smaller PAs and their long-term survival depend on developing appropriate management strategies to maintain their optimal habitats.

The conversion of wetlands and their associated habitat for agriculture and residential development pose a serious threat to the survival of wetland-dependent indicator species such as serval because of habitat loss and discontinuity of wetland. My research identified wetland patches as key for the survival of wetland-dependent indicator species in fragmented landscapes. The long-term survival of such species depends on developing appropriate management strategies that maintain optimal eco-friendly farming habitats with support from local farming communities.

While primarily aimed at gaining insights into population information of otters, I regularly undertake camera trapping surveys in riparian zones associated with various land uses. This additionally provides useful information on mammalian diversity in these systems.

We’ve illustrated elevated population densities of African clawless otters in- and around fly-fishing estates in Mpumalanga – otters evidently exploiting the artificially high prey availability in the region. The otters here are seemingly playing a role in rainbow trout stock losses, which has an obvious economic impact. There are further multiple reports of conflicts between otters and people fishing for subsistence in various parts of Africa – these remain to be studied in detail to ascertain real influences on otter populations and/or the well-being of people.